Do all tick bites cause Lyme disease?

Let's delve into the details of tick bites and Lyme disease.

It’s that time of year when ticks lurk in the backyard, waiting to pounce on both animals and humans. Interestingly, while there are multiple types of ticks, only the common ones, including the Ixodes tick, are known to cause Lyme disease. Ticks are fascinating creatures as they belong to the family Arachnidae, which includes scorpions and spiders. One of the oldest living beings, which have survived since the time of dinosaurs, can live without food for more than 2 to 3 years. They wait for humans or animals to become their hosts, feeding on blood for 3 to 10 days painlessly by producing an anesthetic, much like leeches.

In Northern Virginia and the lovely wooded areas of Loudoun County, these little critters are expanding and creating a menace in the spring and summer months! Did you know that deer play a significant role in the movement of these ticks by carrying them on their backs? The pesky ticks carry bacteria that can cause disease, particularly a type called Borrelia burgdorferi, which is most commonly found in deer ticks. When ticks enjoy a meal of deer blood, they get an extra dose of these bacteria in their saliva, and when they then bite humans, they can pass it along. It's quite a cycle in nature!

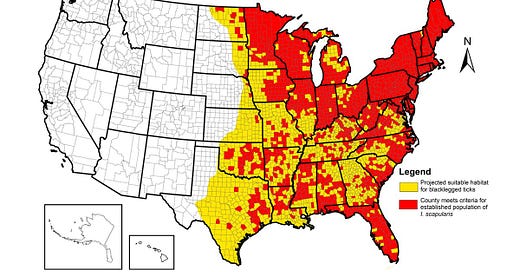

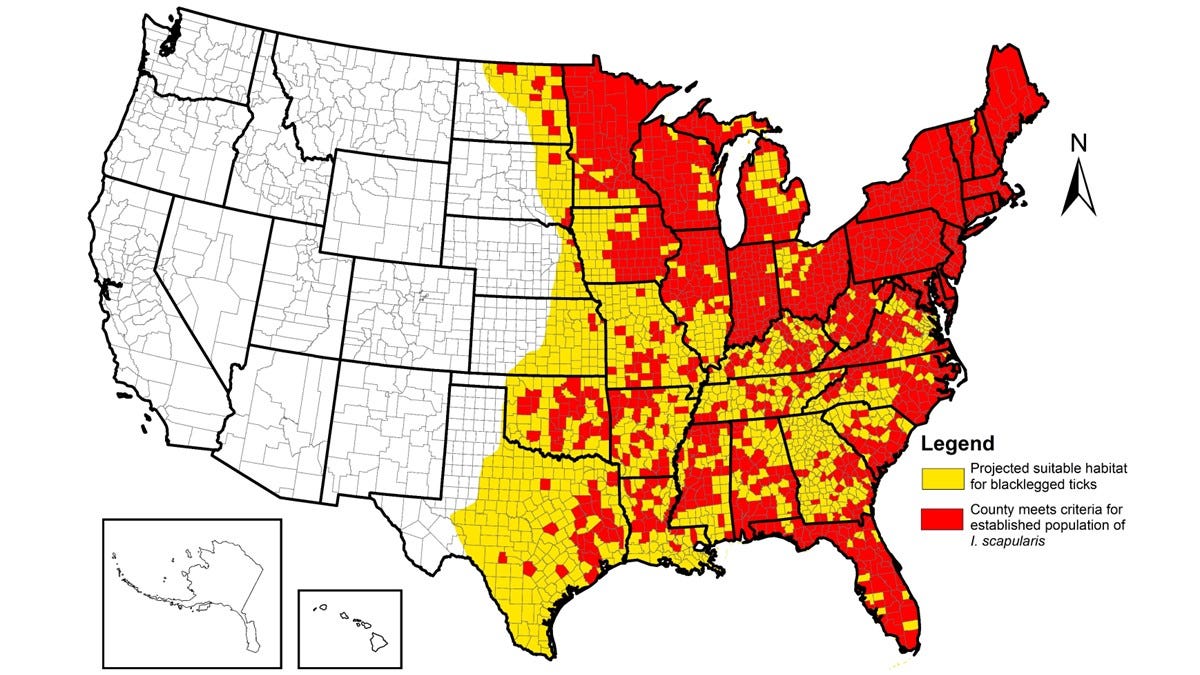

The incidence of Lyme disease in the United States has been increasing; some half a million cases a year have been reported. The great majority of cases occur in New England and the mid-Atlantic states, with additional foci in northern midwestern states (Wisconsin and Minnesota). Less frequently, Lyme disease occurs in the Pacific coastal regions of Oregon and northern California. Although the geographic range of Lyme disease remains limited, it has been expanding. The incidence of Lyme disease is highest among children 5 to 14 years of age and middle-aged adults (40 to 50 years of age), and it is slightly more common among males than among females.

Life cycle…

The primary natural reservoirs for B. burgdorferi are mice, chipmunks, and other small mammals, as well as birds. In the United States, Lyme disease is transmitted primarily by Ixodes scapularis ticks (also known as deer ticks) in the eastern and northern midwestern states, and by I. pacificus ticks in the western United States.

The life cycle of the blacklegged tick, or Ixodes scapularis, which transmits Lyme disease, spans about two years and includes four stages: egg, larva, nymph, and adult. In spring, adult females lay thousands of eggs, which hatch into larvae by summer. These larvae feed on small animals, such as mice or birds; if the host carries the Lyme-causing bacteria, the tick becomes infected. After feeding just once, they turn into nymphs. At this stage, they are notorious for causing severe disease, as they are extremely small and often go unnoticed. After feeding again, they molt into adults, which then seek larger hosts, such as deer, dogs, or humans. Thus, they pose a greater risk in late spring and early summer. By understanding this, one can take protective measures during this time to avoid tick bites.

Pathophyioslogy…

Certain Ixodid ticks transmit Lyme disease, which is the most common reportable vector-borne disease in the United States. The incidence is slowly growing, especially in the northeastern United States. It is caused by Borrelia burgdorferi. There are other counterparts in different parts of the world; however, let's stick with the Lyme-causing bacteria here in the US. The most common sign of Lyme disease is erythema migrans. It starts with a slight redness, similar to a pimple-sized lesion, around the bite site within 3 days to a week, and subsequently enlarges, sometimes reported to occur more than 30 days later. Erythema migrans is a classic bull's-eye lesion characterized by a centrally clearing skin lesion that takes 3-4 weeks to disappear, although it is not always present. As we can see, the different skin redness in the above picture is evident. In some patients, erythema migrans is asymptomatic, but many others experience nonspecific symptoms, such as fatigue, headache, arthralgia, myalgia, and, less commonly, fever. There are other erythema migrans lesions present in Lone Star ticks from the south.

Most patients, around 80%, have a single lesion; however, the bacteria can spread through the bloodstream, causing dissemination hematogenously to other sites. As noted in picture 1C, there are often smaller erythema migrans lesions. Other lesions notoriously caused by the Borrelia species include neurological conditions such as facial nerve palsy or Bell’s palsy, and meningitis that mimics viral meningitis. Additionally, carditis, or inflammation of the heart, can manifest as heart blocks. Arthritis (most often affecting the knee) is a late sign of disseminated Lyme disease, occurring weeks to months after initial infection; it occurs in less than 10% of all cases, because most patients are treated and cured at an earlier stage of the illness.

Diagnosing skin rash (erythema migrans) involves examining the clinical history, recognizing the distinctive features of the condition, and considering any potential exposure to ticks in areas where Lyme disease is prevalent. Like many infections, antibodies formed in Lyme disease can persist for many years. The presence of these antibodies (both IgM and IgG) indicates prior exposure to the bacteria, but it doesn't necessarily mean there is an active infection. Unfortunately, tests that directly detect the bacteria in patients with erythema migrans—such as blood cultures or biopsy samples from the lesion—typically take weeks to yield results, making them impractical for immediate use. This may be especially important in distinguishing between cardiac and neurological issues.

Treatment…

The condition is curable with antimicrobial treatment. Randomized trials have assessed various antimicrobials and found that doxycycline, amoxicillin, and cefuroxime resulted in complete resolution in up to 90% of cases. Once treated, the remaining 10% exhibited mild symptoms of Lyme disease. If the medications mentioned cannot be administered due to allergies, macrolides (such as azithromycin, etc) are suitable alternatives, with cure rates of up to 80%.

In a double-blind, randomized, controlled trial, 180 patients with erythema migrans received either 10 days or 20 days of doxycycline or a single dose of ceftriaxone followed by 10 days of doxycycline. There were no significant differences in outcomes (clinical cure and neurocognitive test results) among the three groups at any of the follow-up evaluations (at 20 days and 3, 12, and 30 months).

Prevention...

1. Avoiding tick-infested areas can be impractical at times, especially for job-related activities.

2. Apply insect repellents (DEET spray) before venturing into the woods.

3. Wear long pants and long shirts to cover exposed skin.

4. Shower after outdoor activities, as ticks can take up to 2 hours to latch onto the skin.

5. Regularly checking your skin for ticks is also ideal.

6. Reducing the number of ticks on your property by spraying acaricides, using tubes that contain cotton balls infused with the insecticide permethrin, and removing leaf litter may help lower the risk.

7. No human vaccine is available yet!

B. burgdorferi bacteria reside in the midgut of ticks. As the tick becomes engorged with blood during feeding, the bacteria replicate and migrate to the tick's salivary glands, from which they can be injected into the host. Studies on the transmission of B. burgdorferi to humans align with studies in animals, indicating that transmission from infected nymphal ticks generally occurs only after 36 to 48 hours of attachment, while transmission from adult ticks happens after an even more extended period (≥48 hours).

In a study comparing doxycycline to placebo in participants bitten by nymphal ticks, where the duration of feeding could be assessed, the risk of erythema migrans in the placebo group was 25% (3 of 12 bites) if the tick had fed for 72 hours or more, and 0% (0 of 48 bites) if it had fed for less than 72 hours. Nearly 75% of deer ticks removed from humans had fed for less than 48 hours.

In a randomized, controlled trial involving individuals aged 12 years or older, a single 200-mg dose of doxycycline administered within 72 hours after the removal of a deer tick was found to be 87% effective (95% confidence interval, 25-98%) in preventing Lyme disease.

For Lyme disease to occur, we need to be exposed for at least 48 to 72 hours. If we identify ticks, take all necessary precautions, and remove them immediately after they latch on, the chances of developing Lyme disease are very low. Often, we may not know how long the tick has been attached. If we notice redness, swelling, or other skin reactions after removing a tick, it's wise to consult a medical professional for treatment. The majority of cases are curable; however, a minority of patients experience chronic manifestations of Lyme disease, and extensive research is ongoing in this area. While there isn't a specific disease process known as chronic Lyme, it is currently called post-treatment Lyme disease syndrome; extensive research is ongoing, which will help clarify the situation.

Tick bites are some of the most common doctor visits in the Northeast during the spring and summer seasons. If you find a tick that seems new and remove it without any skin rash, that generally means there hasn't been an injection of the tick's saliva. As always, it's best to talk to your doctor before making any decisions.

Do all tick bites cause Lyme disease?

The answer is no, especially if the tick is removed within 48 to 72 hours.

References

Lyme Disease, 2014 NEJM, Review article, Shapiro MD

CDC

How Do I Approach the Evaluation and Treatment of Early Lyme Disease? Schutzner et al. 2024

Suman Manchireddy MD

Board Certified in Internal Medicine and Obesity Medicine

Reliant MD Group LLC

Leesburg, VA 20176

Disclaimer: This is for purely informational and educational purposes only. Seek medical advice before starting any testing or treatment regimen. The data presented here has been extensively researched and condensed for a broader audience, and it should be viewed for educational purposes only. The blogger or blog has no affiliation with any pharmaceutical company.